- Home

- Mark Reynolds

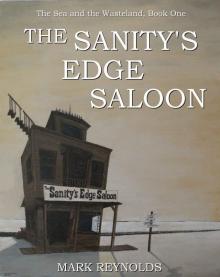

The Sanity's Edge Saloon (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 1)

The Sanity's Edge Saloon (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 1) Read online

The Sea and the

Wasteland: Book I

THE

SANITY’S EDGE

SALOON

By Mark Reynolds

Copyright

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, locations, and events are all products of the imagination, and any resemblance to any actual events or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

The Sanity’s Edge Saloon – Copyright © 1997. This work was first copyrighted in 1997, and filed with the United States Copyright Office in 2001. Subsequent versions of the same title that have been edited by the author are similarly protected under the original copyright.

Cover art and design by Mark Reynolds, Copyright © 2013

Acknowledgements

There are more people to thank than space, but I would be remiss if I did not mention a few. Thanks to those first readers who graciously offered both advice and encouragement: Eric and Katie, and Kerri and Katie. And Dan for asking if I ever considered publishing my book on Kindle. And my parents for instilling in me a love of reading, even if they could never figure out why I liked the strange books I liked. But most especially, I want to thank my wife, Linda. She has always been beside me, my most ardent fan, and I am eternally grateful.

Table of Contents

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

A DAY LIKE ANY OTHER

RASPBERRY-MOCHA LATTÉ

EVERYTHING MUST GO

GONE … BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

CROSS-OVER STATION

THE SANITY’S EDGE SALOON

THE TRIBE OF DUST

HOUSE RULES

ONE

ELLEN MONROE

TWO

MORE GUESTS ARRIVE

THE LINE IN THE SAND

A LESS THAN PLEASANT

GATHERING

UNDER COVER OF DARKNESS

OVERSIGHT

CONNECTIONS

GAMES

OUTCOMES

BETRAYALS

DESPERATE TIMES

THE DUST EATER

THREATS, WARNINGS, AND

ULTIMATUMS

ON A “JAG”

TICKETS, PLEASE!

ONE: THE NOVEMBER WITCH

TWO: MESSENGER

THREE: GRAY PILGRIM

FOUR: PLIGHT OF THE

COMMON MAN

ONE TOO MANY, ONE TOO FEW

THE FACES OF JANUS

THE RED KNIGHT HAS COME

SECRET DOORWAYS - REQUIEM

THE FINAL NAIL

IN THE COFFIN

FOOL’S PARADISE

HIGH NOON

THE CARETAKER

THE LAST TICKET HOME

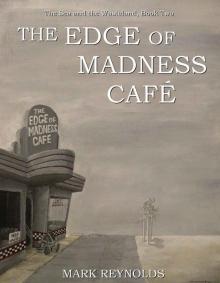

Preview of The Edge of

Madness Café

DREAMS AND REGRETS

A DAY LIKE ANY OTHER

The first day of summer began like any other day, Jack’s routine calcified over time until it gained the permanence of words carved in stone. Awake by six, he got ready for work, donning a drab gray suit, black shoes, inexpressive tie, all per usual. He rinsed his breakfast dishes and left them in the sink; he would wash them up with his supper dishes tonight, and leave them in the rack to dry, so that he could do it all over again tomorrow: just like usual, every morning, five days a week, every week. By ten after seven, he was in his car and headed for Stone Surety Mortgage, and by 7:33 he was parked in the company’s south lot. There was a certain security in routine, in its precision, the semblance of normalcy it contributed to life. Reality become clockwork, order overseeing the tedium of life’s mundane events. And in turn, the clockwork left his mind free to roam the halls of his imagination at will.

For Jack Lantirn, the trade-off was acceptable.

The one great drawback to clockwork is its inherent fragility, the inflexibility of gears and springs. A machine once broken is ruined forever; discarded; replaced. Normalcy reveals itself as little more than an elaborate fabrication, a lie we tell ourselves over and over until it finally loses all cohesion, breaking apart when we believe in it most.

In twenty-eight hours, a bomb placed in the basement of the Stone Surety Mortgage building would explode, debris scattering as far away as a quarter mile.

But today—the first day of summer—was a beautiful day.

Light traffic found him five minutes ahead of schedule staring at a thick layer of gray cloud pushing against the blue sky, the wind already warm and electrified with the approaching storm. He should have called in sick; no one needed a report analyst for a broken company.

In a deal finalized three weeks ago, Stone Surety’s parent company, cash-strapped and lacking any cohesive direction, auctioned off the bulk of the mortgage company’s assets to a lending house based out of South Carolina. The two hundred and thirty-five employees fell on the wrong side of the balance sheet, and were summarily terminated. Those still expected to show up to work everyday either worked very little or very hard; neither had a future with Stone Surety.

Jack Lantirn was a part of the former. Who cared about progress reports or product forecasts when your job was going away? Most of his co-workers were given sixty days off with pay; not for courtesy or kindness, but because state law required it. Two months with a paycheck. Start your job search. Take a vacation. Paint your house. Just go away.

Jack was not so fortunate. He was at work on this particular Tuesday, the first official day of summer, absently tending a dying job.

He entered through the loading bay like always. The door—normally locked and accessible only with an employee ID card—was blocked open to accommodate the movers loading a semi in the bay with banker’s boxes of mortgage files; what was loosely termed “assets.” He walked past rows of empty cubicles once loud with telemarketing reps; management saw no reason to keep them around. Jack, apparently more trustworthy, was expected to come in for eight hours a day on the off-chance someone had a report-based question about numbers that no longer mattered.

The funny thing about being trustworthy, he realized, was that it wasn’t a compliment. It meant that you were afraid, that you wouldn’t step out of line or do anything unusual, and could be trusted to do exactly what they expected. And on that last day, when the company expected him to walk away without raising a fuss, he would probably do that, too.

The only thing worse was the realization that they were correct.

A large dry-erase board greeted him at the end of the empty cubicles, a stark contrast of naked white but for a single, inelegant phrase hand-printed in violent green: TODAY IS TUESDAY. Where once the board would have been occupied with lists and plans and assignments for the coming week, month, year, now there was nothing but emptiness. It might just as easily have said that the day would be no different than any other he was doomed to exist through, the same as yesterday and the day before and the day before that. It might have promised that today would be repeated over and over and over until he went completely insane. It might have said all that and been true. But this way was simpler.

It was also a lie. Each day was a day closer to unemployment. Soon he would be reading want-ads, cold-calling companies, asking anyone and everyone he knew if they had heard of any openings, and could they let him know about any job-postings they might come across. Eventually money would run out, and he would get some desperate job that paid less, made him work more, and put off his dreams of being a writer a little longer. Just thinking about it made him feel sick.

So he tried not to. Denial. For now, for today, it was a day like any other.

In twenty-eight hours, a cardboard box containing one

hundred and fifty sticks of dynamite would explode near the gas main in the basement of the Stone Surety Mortgage building. The detonation would obliterate most of the building and those inside of it in what authorities would call the most devastating singular bomb blast on American soil since Oklahoma City.

But not for another twenty-eight hours.

Jack spent the next forty minutes in the cafeteria, killing time before the start of his shift, writing and drinking mediocre coffee served from a vending machine. In its heyday, the company employed over seven hundred people, the cafeteria serving both breakfast and lunch. The cafeteria closed a year ago during the first round of layoffs—you should have seen this coming, then, you know—leaving only the vending machines behind.

I just want to be a writer.

He was working on his book; it seemed so much more important now. Writing was what he did: for himself, for his sanity, for no other reason than he hoped to be a real writer one day. But writing didn’t pay. Truth be told, it probably cost more in time and money than it was worth. He’d heard stories of first-time writers getting fat advances from publishers; of semi-literate pop icons releasing bestsellers into the market; exceptions that proved the rule. If he wanted to continue eating and paying rent, he needed a job.

Dreams could wait.

Through the cafeteria’s wall of windows, he looked at the early morning sun golden on the lawn of Stone Surety Mortgage, the summer grass still new and bright, begging the question: What’s stopping you from leaving? From simply getting up from this chair, and walking out the door, and never coming back? Not to your job or your apartment or anything? A dozen steps. Twenty at the most. Open the door and just walk away. It would be a whole different world then, wouldn’t it? So what’s stopping you from simply leaving?

The question occurred to him more and more often. And more and more often, he had trouble coming up with an answer.

They officially announced Stone Surety’s closure a week ago Monday, most of the immediate terminations taking place Wednesday afternoon. By Thursday morning, Jack had ten pre-programmed phone numbers that rang dead lines.

And on Friday, Jools left.

Technically Jools left sometime Saturday morning, but it was over on Friday.

They met every Friday at Finnegan’s Pub for dinner, part of his comfortable clockwork routine. Jack arrived early—there was nothing at the office to occupy his time or keep him late—and saw Jools sitting with someone, sitting too close, laughing too comfortably. Then he leaned towards her—this man she was with—and they kissed. Jack watched it all from across the room, not knowing what to think, how to feel, what to believe. There was only emptiness, a void of thought and emotion. He was actually prepared to dismiss it as nothing, his misunderstanding: this other man is just a friend, a relative perhaps, and Jools is affectionate; demonstrative; a kiss means nothing. After all, she’s your girlfriend. Six months now. Hardly a lifetime, but it means something. He should—

Jools leaned into the stranger’s kiss, eyes closed, the space between them disappearing.

… should …

And six months evaporated in an instant—a meaningless waste, empty time—as two lovers kissed in a bar, her hand brushing a stranger’s cheek, his fingers caressing her hip with dreadful familiarity.

… should …

Then she looked up and saw him; saw him standing there, watching, doing nothing.

And it actually got worse.

Her expression held neither surprise nor guilt, only resignation and something like pity.

Jack nearly collided with the doorframe as he tried to escape, pulse deafening, hands weak and trembling. He wandered uneasily to his car and drove home in silence, hands gripping the wheel so tightly that his knuckles ached. Back in his apartment, he collapsed into a chair as the last drop of strength poured out of him. This must be what it feels like to bleed to death, he thought, the notion both romantic and ignorant, and he sat there in the swelling darkness, nursing his own misery. He needed Jools to be there for him; selfish perhaps, but what was the point of love if you couldn’t depend on it when you needed it?

This notion was similarly romantic, and just as ignorant.

He never particularly cared about his job, but he genuinely cared about Jools. Jack was a long-haired dreamer doomed to be utterly ordinary, utterly forgettable, a hapless victim of mediocrity. But Julie Eden—she nicknamed herself Jools because it sounded exotic—was anything but ordinary. Beautiful. Bright. Exciting. She even had a tattoo. What she saw in him, he never really knew, and he never thought too hard on the subject.

It would have surprised him to learn that Julie Eden was actually a romantic, a believer in the adage that still waters run deep. A self-professed writer, Jack sounded exciting at first. Unrealized potential. Raw clay to be molded and shaped, his inner qualities coaxed to the surface. But when Jools reached into the pool that was Jack Lantirn, she made a disappointing discovery: it wasn’t really all that deep. She’d tired of the labor, and decided to move on to more willing clay, more realized potential.

All dreams end eventually, and we wake up.

If he was being honest with himself, which was rare, Jack supposed he did not love Jools so much as he loved the idea of Jools; that glimpse into another life, a more pristine life of sated wants that writers and artists deserved. But that same honesty would force another revelation he was even less prepared for: he was not a writer or an artist. He was no one. Nobody. Nothing. When you cut through the bullshit, Jack was a writer who had never been published, not once, not even in a school paper or some local literary magazine with a circulation of less than a hundred.

Her disillusionment was understandable, her betrayal not unexpected—if he was being totally honest with himself.

But that was rare.

She walked in, finding him alone in the darkness; he’d given her a key two months ago, that eager to believe it would work. “Jack? Can we talk?”

He didn’t answer.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t want you to find out like that.”

“How did you want me to find out?”

Light from the street-lamp outside turned her to shadows and lines. “I wasn’t really sure how to tell you. This isn’t easy for me.”

Amazing! He wasn’t aware he was supposed to make it so.

“I … I guess I just thought it would be different. When you told me you were a writer, it sounded kind of exciting, you know. I guess it was silly of me to think that.”

“I’m sorry to disappoint you.” He had hoped the remark would sound venomous and scathing, but realized it came out very much like an apology.

“It wasn’t you, really. I just expected more. For a while I thought I could deal with it, but I can’t. I’m sorry you found out about it that way, though. It wasn’t fair.”

“Neither’s life,” he remarked. “I’m getting used to it.”

“Please don’t hate me.”

And the break in her voice just then was the cruelest thing he could ever have imagined. Cruel because it held out the illusion of hope. There was just enough light in the room to see tears on her cheek, making him regret the hurtful things he had said—or meant to say—make him want to comfort her, hold her in his arms and press her head to his shoulder, feel her warmth against his skin, even …

“I don’t want to end this with you hating me,” she said, stepping closer, kneeling down in the chair over top of him, straddling his lap. “Please say you won’t hate me, Jack. Please.”

He shook his head, unable to say anything. In that moment, he concocted elaborate myths of how she would fall back in love with him, how she would see his commitment to her and forget this other guy, make love to him tonight, and stay with him forever, and everything would be as it was.

She leaned down to kiss him, a deep, aching kiss like none he had ever had before, and for a brief time, he believed his own fiction.

The next morning, he woke alone in the gray light of predawn, tangl

ed in sweat-soaked sheets. Beside him was a note left upon the pillow, very trite, very cliché. It said only:

Jack, I’m sorry. Please don’t hate me. I will always love you.

Jools

He had forgiven her. He had promised her he would not hate her. He had cleaned her Karma in exchange for one night of bliss, and so she left, free to pursue her life without him.

Jack Lantirn, prince of fools.

So he wrapped himself in his writing, retreated into his routine, and hoped that through an imitation of normalcy he might in some way influence its return. He was the primitive stamping around the fire, petitioning the night sky to end the plague visited upon his house and casting chicken bones and goat’s blood into the blaze. Only this primitive dance was called the daily grind, his routine. No extended lunches or long coffee breaks; that wouldn’t have been normal. Bored at his desk, he loaded his writing into the computer and worked on it every day, trucking it back and forth on a thumb drive. His routine would save him from going mad, from losing his mind, from standing up and walking the hell out of everything. What is keeping me here? The routine. The routine would bring back normalcy; it would bring back the reality he had learned to cope with.

These were the lies he made himself believe.

He wrote a page and a half in long-hand before heading up to the pre-fabricated, mauve walls of his cubical where he started his day as usual, turning on his computer.

No, not his computer. Not really. No more than it was his cubical, his files, or his reports. None of this was his. It was all borrowed, his privileges on the verge or being rescinded. Sixty days, and not a day more. Please surrender your ID card upon exiting the premises.

He loaded the story from the thumb drive he carried—this, at least, was his—and started typing in what he had written in the cafeteria.

A winter storm rolled across the city, snow twisting down from the leaden skies, eddies of wind creating cascades of great crystal helices like strands of DNA collapsing under the onslaught of some new viral strain.

The Sanity's Edge Saloon (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 1)

The Sanity's Edge Saloon (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 1) The Edge of Madness Cafe (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 2)

The Edge of Madness Cafe (The Sea and the Wasteland Book 2)